Before the next heat wave, read this

Plus: What happens when the power goes out during a heat wave + What’s “resilience”? + Do I really need 10,000 steps a day?

Welcome to Doing Well. Today:

A doctor shares how heat affects our bodies

A game to prepare for hotter days

Word(s) of the week: resilience

Health news we’ve found useful this week

Unpack the 10,000 steps a day goal

Happy June! Let’s get started.

We Asked: How can we protect ourselves from summer heat?

As summer settles in, so do dangerously high temperatures that pose serious health risks. Hundreds of thousands of people die every year from heat illness, making heat the deadliest form of extreme weather. Experts believe the true number of heat-related deaths is likely much higher than we realize. So, how does heat actually affect our bodies, and what can we do to protect ourselves and our families?

I spoke with Dr. Pope Moseley, a physician and biomedical sciences researcher at ASU’s College of Health Solutions, about how heat can amplify underlying health conditions and what to know about heat-related illness. Our conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

Natasha Burrell: You've previously discussed how when there's a heat wave, the hospital fills up not just with heat-related illnesses, but also other conditions like heart attacks, strokes, and dementia. Can you explain how heat makes these illnesses worse?

Pope Moseley: Heat is the first multiplier of illness. There are many conditions that are made worse by heat; heat does a number of things. First, heat can cause you to become dehydrated. You sweat more—but you need to replace that fluid. If you're not replacing fluid, you can pump out liters of fluid to try to cool yourself. When you do that, then your body doesn’t have the blood volume to pump [blood] to various parts.

Not only can dehydration lessen the amount of fluid you have, but we don't have sufficient blood to fill all the tubes. So your body is always making choices of where to send that blood. The brain always gets a big share, heart, kidneys—but when you have, for example, working muscle, there's a lot more blood going to the muscles than normal, and the body has to make choices about where it's taking the blood from. When you're cooling yourself, you can have half your blood volume going to your skin. When you start having demands like cooling through the skin, especially if you're exercising, that pushes blood away from other organs. The biggest organ that's affected is the gut. Your [gut] bacteria produce a lot of compounds that are really important for you to function, including a lot of neurotransmitters. So if you start pulling blood away from the gut, a lot of things happen, including the gut bacteria change, and can cause huge disruptions.

All of these changes that are heat driven affect organs that are not working at tip-top shape. Imagine someone who has a heart that is teetering because it has just enough blood coming into it to pump, to work efficiently. So if you suddenly have to push half your blood volume out to your skin, you can have a failure of that organ. That's why so many diseases are impacted.

There are [also] a whole bunch of medications that can cause you to lose fluid, like diuretics. Many drugs for depression and anxiety, for instance, can make you more heat sensitive.

NB: What is heat illness? What are the signs and symptoms?

PM: There is one group of diseases where you get progressively more dehydrated and your body temperature begins to rise. You develop heat cramps because of electrolyte abnormalities. That's called heat exhaustion. That's one group of diseases.

There's another disease called heat stroke. People like to think of a continuum of heat cramps, heat exhaustion, heat illness, then heat stroke, but that's not the way it works. There's a bunch of dehydration-related diseases, and those are progressive. Heat stroke itself is an explosive, catastrophic illness—you have sudden collapse. It can happen in an exercising person within 15 or 20 minutes. What happens, especially in unconditioned people or people not used to the environment, is you can get this endotoxin leak across your gut. Your liver fails, your kidneys fail; you develop respiratory distress, and your blood no longer clots. This isn't one of those things where you can go hiking and say, Well, I better drink some more water because I'm kind of feeling tired and ill. You can develop an explosive heat illness. The primary problem with heat stroke is loss of mental function, so you don't think well. This is what happens in the Grand Canyon where somebody's hiking and suddenly they go down. They've had this explosive thing and they don't know it's happening until they're too far gone. The mortality range is between 20 and 60 percent. In the best case scenario, you have a one in five chance of dying. So I'm very careful in the heat.

NB: As we head into the hottest months of the year, what advice would you give to someone managing health conditions that can worsen in extreme heat?

PM: When it's a little bit cooler, you can take yourself through heat acclimatization. When you expose yourself to heat on a daily basis for a week or two, you get more heat adapted. I wouldn't recommend going out on a 120 degree day and trying to undergo that process, but I would suggest that you think about taking a walk when it's cooler, or going outdoors when it's in the 80s to let your body slowly get used to heat. Heat acclimatization is the ability to sweat more—you start sweating at a lower temperature, so you start cooling your body earlier than you would if you're not acclimated. Exercise is a great substitute. For heat exposure, exercise generates the same kind of changes. If you decide that you're gonna start a new exercise program in July and go outside and run, that's not so great.

NB: I’ve noticed people hiking up a mountain with just a single bottle of water; does that pose a risk?

PM: Even an acclimatized person can easily sweat well over a liter an hour. You can push all that fluid out very quickly. You need to carry water and you need to realize that in those situations if you don't feel right, you’ve got to stop. You've got to cool yourself because this is a multisystem vascular collapse and you can crash pretty quickly. I've taken care of a number of people where you resuscitate them, but then they die in the ICU over the next two or three days because they have this irreversible inflammatory response.

NB: Here in Arizona, we often hear, “It's a dry heat.” Do different types of heat—dry versus humid—affect our health differently?

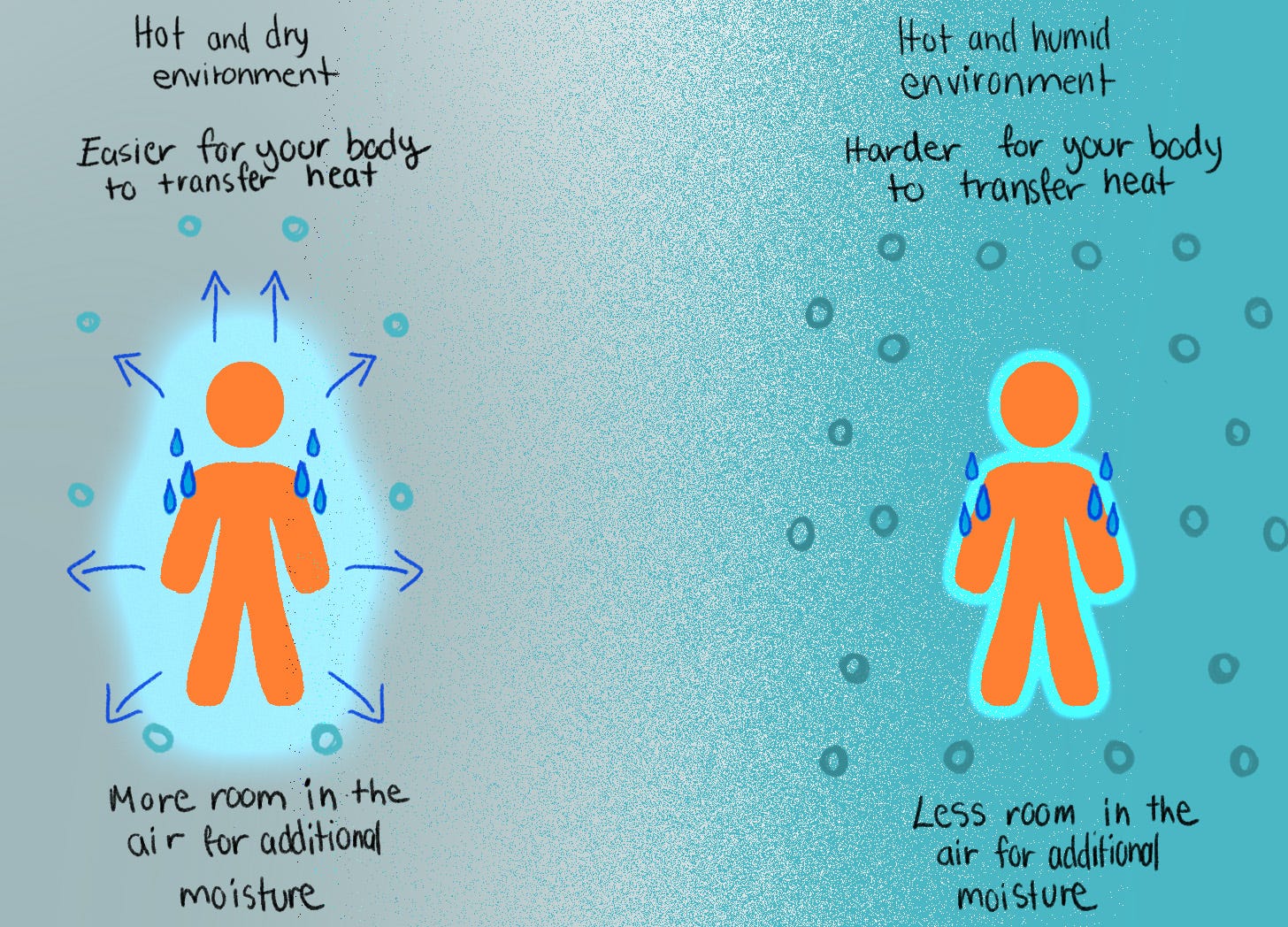

PM: You have to transfer heat to the environment. So when your body temperature is 98 degrees, [and] the air temperature is 100 degrees, the only way you're transferring heat is through evaporative cooling [for example by sweating]. If your evaporative cooling gets impaired, you can't transfer heat anymore to the environment. What blocks [heat] transfer? Well, one thing is if you're dehydrated. Another is humidity. [When there is] humidity in the air, you can't rapidly move water from your body up to dump energy, then you can't cool.

NB: What other tips do you have for people who have no choice but to be outdoors, whether for work or daily life? How can they best protect themselves?

PM: Wear a hat, wear long sleeves, seek shelter—even if it's just shade. Continue to drink water because not only does water give you more to evaporate, but when water hits the stomach, temperature drops. Go to cooling centers. It's really hard—heat is not only the first multiplier of disease, it is the first multiplier of social conditions.

Well-Informed: Related stories from the ASU Media Enterprise archives

In this essay for Zócalo Public Square, writer Caroline Tracey explores an overlooked consequence of climate change: boredom. She examines how heat-induced ennui could become a force for climate change activism.

Plus: How will extreme heat change our cities—and our relationships—in the future? In a new short story from the Future Tense Fiction series on Issues in Science and Technology, writer Harrison Cook imagines a heat-sieged city where most residents have become functionally nocturnal. We meet an essential worker tasked with laboring during the day to fix private shade structures designed to provide shelter from the grueling sun for anyone who can pay. When the worker discovers someone is sabotaging the structures, he faces a dilemma—and then, a heat-induced emergency. In a response essay, Pope Moseley argues we need to confront our extreme heat problem at its roots.

Well-Versed: Learning resources to go deeper

Test your coolness under pressure with Beat the Heat, a fun and free online game from Ask A Biologist. Learn practical ways to stay safe in hot weather while exploring, solving challenges, and navigating extreme heat. How long can you stay cool?

Looking to learn more about heat and health? In these Health Talks from the College of Health Solutions, experts discuss climate-driven heat trends and solutions to reduce health risks for the most affected populations.

Well-Read: News we’ve found useful this week

“A Ministroke Can Have Major Consequences,” by Paula Span, May 27, 2025, KFF Health News

“Americans Don’t Eat Enough Fiber. Here’s Why That Worries Nutrition Experts,” by Andrea Petersen, May 25, 2025, the Wall Street Journal

“Drowning is the Leading Cause of Death in Young Kids. Here’s How to Prevent It,” by Katia Hetter, May 24, 2025, CNN

“The MIND Diet May Help Reduce Alzheimer's Risk, a Large Study Shows,” by Linda Carroll, June 2, 2025, NBC News

Well-Defined: Word of the week

You may have heard the term “resilience” in conversations about mental health. Child development researchers define resilience as the ability to adapt well in the face of adversity (hardship), trauma, or tragedy. For example, a child with cancer who recovers and goes on to live a healthy life is mentally and physically resilient. Children are labeled resilient when they defy expectations for a negative outcome.

Critics of the popularization of the term “resilience,” including Tracie Washington of the Louisiana Justice Institute, suggest the term puts the responsibility for adversity on the individual. This could distract from and excuse the larger systemic reasons for the adversity in the first place and potentially blame individuals for outcomes outside their control.

Fundamentally, we all have the capacity to demonstrate resilience, and there are ways to increase your capacity. Talk to older members of your community about their life experiences or watch young children climbing up a jungle gym—this can help you gain connection and perspective. Engage in deeply meaningful and supportive relationships that challenge you. Building resilience is contagious.

- Elizabeth K. Anthony, Associate Professor, ASU Watts College of Public Service & Community Solutions, School of Social Work

Well-Aware: Wait … how many steps should I get in a day?

If you’re on social media, you’ve likely come across the “Walk 10,000 steps with me by 10 a.m.” trend. I’ll be honest: When I first saw it, I felt a little disheartened. I struggle to get 10,000 steps in an entire day, and someone is accomplishing that by 10 a.m. What am I doing wrong?

It turns out 10,000 steps isn’t a magic number, and fitness isn’t one-size-fits-all. That number originated from a marketing campaign to boost sales of step counters (also known as pedometers). In 1964, a Japanese company called Yamasa released the first pedometer named manpo-kei, which translates to “10,000 steps meter.” The idea stuck.

Research from the Mayo Clinic and Harvard shows that movement is essential for health—but you don’t need exactly 10,000 steps to see benefits. Small, consistent efforts that fit your lifestyle can be just as impactful. This could be walking to nearby places instead of driving, parking further away from an entrance, or taking your dog for a stroll around the block.

So, what should we aim for? Set a goal that feels achievable and sustainable for you. As TED-Ed educator Shannon Odell explains, even small increases in our daily steps can improve both our physical and mental health.

The next time you scroll through social media and come across a viral fitness trend, remember: You’re not doing anything wrong. The daily movement that works for you is enough.

- Kitana Ford, health communication assistant and ASU student

Do you have a question or topic you’d like us to tackle? Would you like to share your experience? Reach out at any time—we’d love to hear from you.