How to keep your brain young

Plus: What’s a patient advocate? + Tips for emotional regulation + A surprising fact about health in Arizona

Welcome to Doing Well. Today:

New cases of dementia are on the rise—what research says about risk

Tools to help preserve your family’s story

Word(s) of the week: “patient advocate”

A reporter shares a surprising fact about health in Arizona

Happy Tuesday. Let’s get started!

We Asked: How do our brains age—and what can we do to keep them healthy?

As we age, so do our brains. But how quickly our brains get older depends on a complex tangle of factors related to genetics, environment, and behavior, some within our control, and some outside it. Perhaps you’ve met a 90-year-old with a better memory than your own—a great example of how each brain is unique, moved and molded by circumstance.

While brain health—also known as cognitive health—is highly individual, there are things we can all do to improve our own. I spoke with Yi-Yuan Tang, a neuroscience professor in ASU’s College of Health Solutions, to explore his research on brain aging and the powerful link between mindset, mindfulness, and brain health.

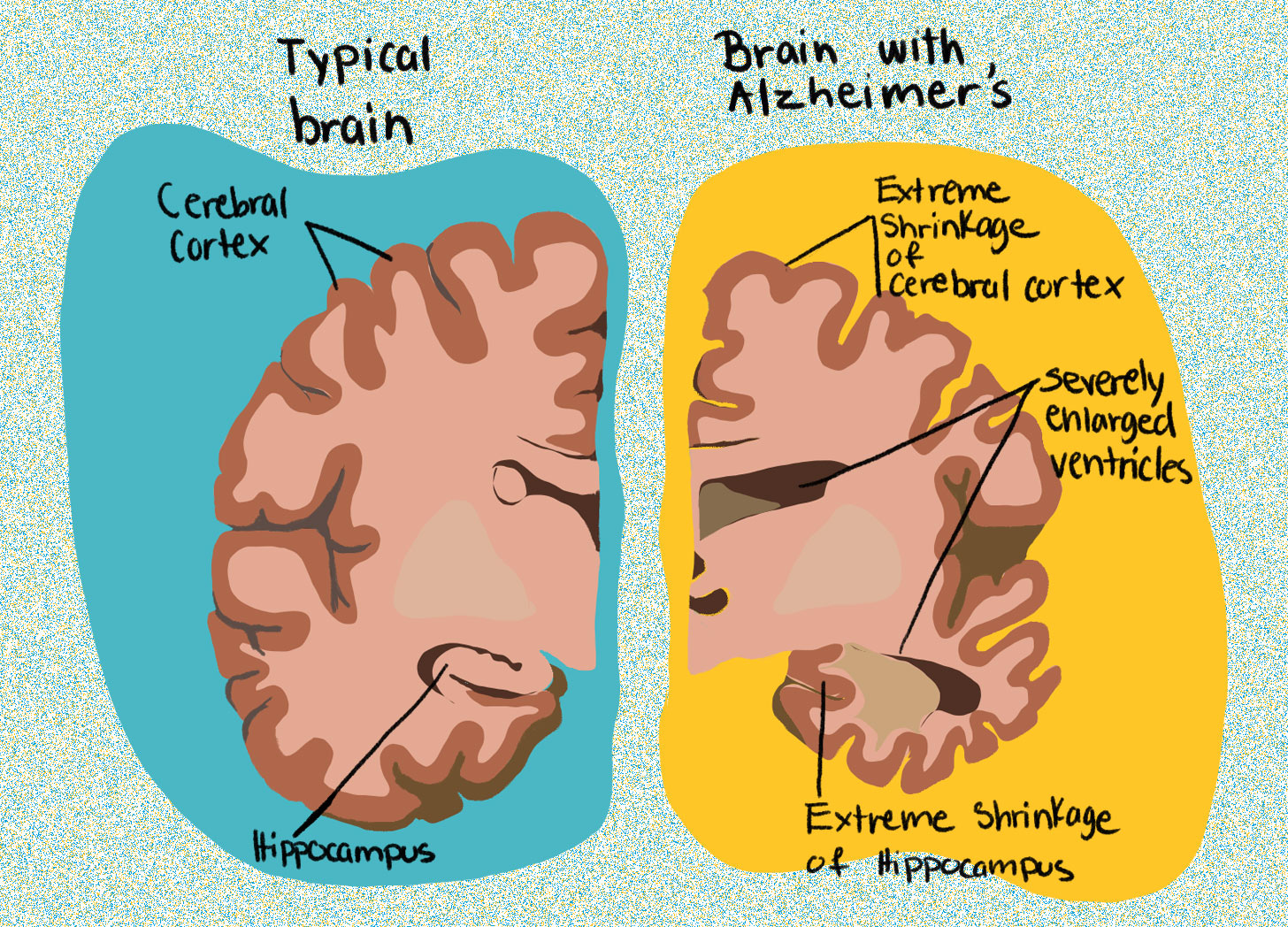

We also discussed dementia—a term that refers to various brain conditions that involve loss of memory and other cognitive (thinking) skills. The most common form of dementia is Alzheimer’s; according to the Alzheimer’s Association, more than 7 million Americans 65 and older live with the condition. Our conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

Mia Armstrong-López: Many of us are familiar with how our bodies age. When and how do our brains age?

Yi-Yuan Tang: We usually believe that for people 65 or older, brain structure starts to shrink. However, recent studies also show that can be true even for people in middle age. The latest studies find brain age depends on white matter and gray matter, and these two structures actually age early, so our brains age earlier than we thought.

MAL: What factors determine how quickly our brains age?

YYT: Our genetics can really influence how our brains age. If a person has what’s called the APOE4 gene, this gene is a risk gene for aging and Alzheimer's. In the U.S., about 20 to 30 percent of people are APOE4 carriers—they may have a risk of aging faster, or Alzheimer's.

If you go to Asia, Europe, or Africa, they have different proportions of APOE4 carriers compared to the U.S., so we would expect they may have a higher risk of Alzheimer's and brain aging. But actually, the risk is similar. So research finds lifestyle and environmental factors also play a role.

When people live in a very poor environment—low nutrition, low socioeconomic status—and have early life adversity or high stress, studies show those factors will influence brain development and contribute to brain aging.

Another part is lifestyle—more screen time, inactivity, and more stress also contribute [to brain aging].

MAL: There are certain things that are outside of our control, like genetics and socioeconomic status. But what are some attainable lifestyle changes that could make a positive difference?

YYT: Lifestyle can really drive our health and contribute to brain health and aging. Lifestyle is pretty broad, including exercise, nutrition, stress management, and healthy mindset.

At the cognitive level, people should have a healthy mindset. Let me give an example. There was a study done by Harvard University with housekeepers. They told one group of housekeepers: Every day that they work for eight hours (cleaning hotel rooms) is good exercise and satisfies the Surgeon General’s recommendations for an active lifestyle. For another group, they just said, exercise is important.

The first group changed their mindset: Oh, my daily work is exercise. After four weeks, this group reduced their blood pressure, body weight, and body mass index.

For the emotional part, people often link stress and negative emotions together. So in the health neuroscience field, we teach people how we can regulate daily emotions, and how to handle emotional fluctuation.

MAL: What are some tactics to regulate emotions?

YYT: Let me give you a metaphor. If we are at the bottom of the mountain, we see there's one way we can climb to the top—that's the perspective. When we climb to the top, we see, Oh, my goodness! There’s a shortcut. This is a perspective change.

People think, When I'm stressed, my heart beats faster, my breath is shallow, and my muscles tense. In our mind, we believe stress is not good. But stress can actually give us a challenge. If we change our mindset a little bit—Oh, stress makes me move faster, can give me more oxygen, more blood to the brain, I can do better—this small change allows people to say, Oh, stress is not always bad.

There’s a cognitive strategy called a reappraisal—reinterpret the situation, then change the mindset, which influences emotional response. Here is an example: Somebody was very rude to you today. You feel unhappy—a negative emotion. You need to reinterpret the situation. You say, Oh, the person is having a bad day. They may have had something very bad happen in their life. I understand. You reinterpret the situation, so your emotions change.

MAL: Your research shows mindfulness can help us with these mindset shifts. How?

YYT: Mindfulness is about being present without judgment. You pay attention to the present, whatever arises or disappears in your mind, and you are aware of and accept it: OK, this is my stress, this is my emotion—part of my life experience. You just observe, you are aware. You create some space between the stressors, the emotions, and yourself—“you” being someone who can notice or observe all these things. If you want to fight with your stress, fight with emotions, and even fight with your thoughts, you will never win. Research shows our emotions fluctuate all the time. Our stress response is not only stress—it’s linked to the body and emotions.

MAL: Let’s think about an example for people who are interested in mindfulness, but aren't sure how to practice it. Imagine I'm at work, and I get an email from my boss asking me about the status of a project that I'm behind on. I feel a stress response in my body. What would be a mindful approach to that situation?

YYT: So when you get an email—a trigger—your body has a sensation of stress. Guide your attention back to your body, to that sensation: OK, I’m aware I'm nervous, I'm stressed. Where? Maybe on my shoulder, my neck, maybe my heart. So you pay attention to that part—don’t change or suppress anything, just be aware and open up to the experience: OK, this is my sensation, it may relate to stress. Usually after a few minutes, you find something changes, because the sensation of stress often comes and goes. You can tell yourself, OK, I can pay attention to my body part—can I further relax that part? In my health neuroscience class, students often practice mindfulness together for three to four minutes, and they immediately feel relaxed, calm, and less stressed.

MAL: Lots of people might think—I would love to do mindfulness, I would love to focus more on emotional regulation, but I don't have time. But with the research on how closely this is linked to brain health and aging, we should treat it as an integral part of our routines and our overall health.

YYT: Exactly. It's the key message: If you think something is important, you always have time; if you don't think something is important, you never have time.

Well-Informed: Related stories from the ASU Media Enterprise archives

Over 40 years, new cases of dementia are projected to double in the U.S.—from around 500,000 in 2020 to 1 million in 2060. Jessica Langbaum, codirector of the Alzheimer’s Prevention Initiative at Banner Alzheimer’s Institute, joined Arizona Horizon on Arizona PBS to discuss the trends in dementia and cognitive aging, and what research tells us about reducing risks. “Keeping yourself challenged and socially engaged, active, those are all important—but not one of those things is a cure,” she says.

Plus: Her mother’s Alzheimer’s diagnosis led Alva Rodriguez to a job as a caregiver in California’s In-Home Supportive Services program. In an essay for Zócalo Public Square, she describes the challenges of caregiving work, and the changes needed to give more support to workers and the people they care for.

Still looking for more? Read Yi-Yuan Tang’s breakdown of when and how our brains age and what we can do about it in State of Mind, a collaboration between ASU and Slate that covered mental health.

If you’re looking for Alzheimer’s support and research in Arizona, visit the Arizona Alzheimer’s Consortium website.

Well-Versed: Learning resources to go deeper

Everyone has a story—how do you tell yours? Join Duane Roen and ASU Learning Enterprise to learn how to preserve your family's memories and stories. You’ll find free prompts to ask yourself and loved ones, and you can start writing your story today.

Well-Read: News we’ve found useful this week

“A Study Finds Stacking Bricks Differently Could Help This Country Fight Air Pollution,” by Jonathan Lambert, May 18, 2025, NPR

“Nine Federally Funded Scientific Breakthroughs That Changed Everything,” by Alan Burdick and Emily Anthes, May 16, 2025, The New York Times

“Online and Pregnant,” by Lizzie O’Leary and Amanda Hess, May 11, 2025, What Next: TBD

“New Guidance Calls for Pain Relief During IUD Insertion,” by Maya Goldman, May 19, 2025, Axios

Well-Defined: Word of the week

Have you ever sat in a doctor’s office, struggling to understand your diagnosis or treatment plan, wishing someone could explain it more clearly? A patient advocate can help. Patient advocates act as a bridge between you and your health care providers, helping you understand and manage your care. They can also review your medical bills and insurance statements to ensure accuracy. With an advocate’s support, you are better equipped to make informed decisions, stay in control of your health, and feel confident throughout your treatment and follow-up care. If you find yourself in need of a patient advocate, use this tool to review your options.

-Kitana Ford, health communication assistant

Well-Connected: Behind the scenes of health care

We asked Stephanie Innes, a health reporter with the Arizona Republic focused on health policy and patient experiences: What is one thing you've learned while reporting on health that you think everyone should know?

Arizona has a severe provider shortage. It's almost impossible to find a good therapist right now in Arizona, especially if you are looking for one who takes insurance. It's also really difficult to find a primary care doctor and a lot of people don't have one for that reason.

The provider shortage is fueling existing challenges to navigating health care. Health insurance is not consumer friendly, and it can be particularly frustrating if you become ill.

We also asked: What is one thing that you think would surprise readers about health in Arizona?

Millions of people in Arizona are getting their health care paid for by the government, but I'm not sure all Arizonans realize that. … when the 2 million Arizonans covered by Medicaid are combined with the approximately 1.4 million covered by Medicare, that's nearly half the state's population covered by government health insurance. Medicaid, which is primarily for low-income people, covers about one in four Arizonans and pays for nearly half of the state's births. I find that the people I interview or just interact with in daily life are often surprised by that.

Stephanie’s answers were sent via email and edited for length.

Do you have a question you’d like us to ask an expert? We want to hear from you.