They make up one-third of U.S. births. Here’s what you need to know about them.

Plus: How to discuss stressful medical decisions before they happen + What’s “prophylactic”? + A tip to improve sleep

Welcome to Doing Well. Today:

A Q&A on the history of C-sections in the U.S., and how to talk to your doctor about your birth priorities

An article on what happens when hospitals face cyberattacks

A tool to learn more about the science of embryos, development, and reproduction

Health news you should know this week

A tip to improve your sleep

Word of the week: prophylactic

Breaking down the myths surrounding mental illness and violence

Let’s get started.

We Asked: What should everyone know about C-sections?

During an unplanned Cesarean section for her first child, Rachel Somerstein was not properly administered anesthesia. As a result, she could feel the procedure in excruciating detail—an experience that left her with post traumatic stress disorder, or PTSD.

When anesthesia is correctly administered, a patient would not feel the operation in the way Rachel did; C-sections are incredibly common surgeries that thousands of American women go through each day. But in the aftermath of her procedure, Somerstein, a journalist, began reporting on the complex, tangled history of C-sections, and how mothers experience them. This reporting eventually turned into Invisible Labor: The Untold Story of the Cesarean Section—a book in which Rachel tells her own C-section story, and the story of the procedure in American life.

I spoke to Rachel about what we should all know about C-sections and advocating for ourselves in complex medical situations. Our conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

Mia Armstrong-Lopez: What did you know about C-sections before you had one?

Rachel Somerstein: Very, very little. I skipped over those parts of the pregnancy books. I knew I didn't want to have one, but the reasons I thought I didn't want to have one were not very good reasons. There are many reasons why a person might want to avoid having a preventable C-section, but I just had this stigma associated with the operation, this hangup that if I weren't to have a vaginal birth that would mean something about my character. And for that reason I was like, Oh, I'm not gonna have one. And nobody really disabused me of that; my providers didn't really talk about it.

There are many things about that that are problematic. [C-sections] are 1 in 3 births in the United States. So just from numbers alone, it's a very real possibility. It's more real than the other pregnancy complications we talk about, like preeclampsia or developing gestational diabetes.

I should have at least known: This is what happens in a C-section, and this is what it's like to recover, and my provider should have suggested that to me.

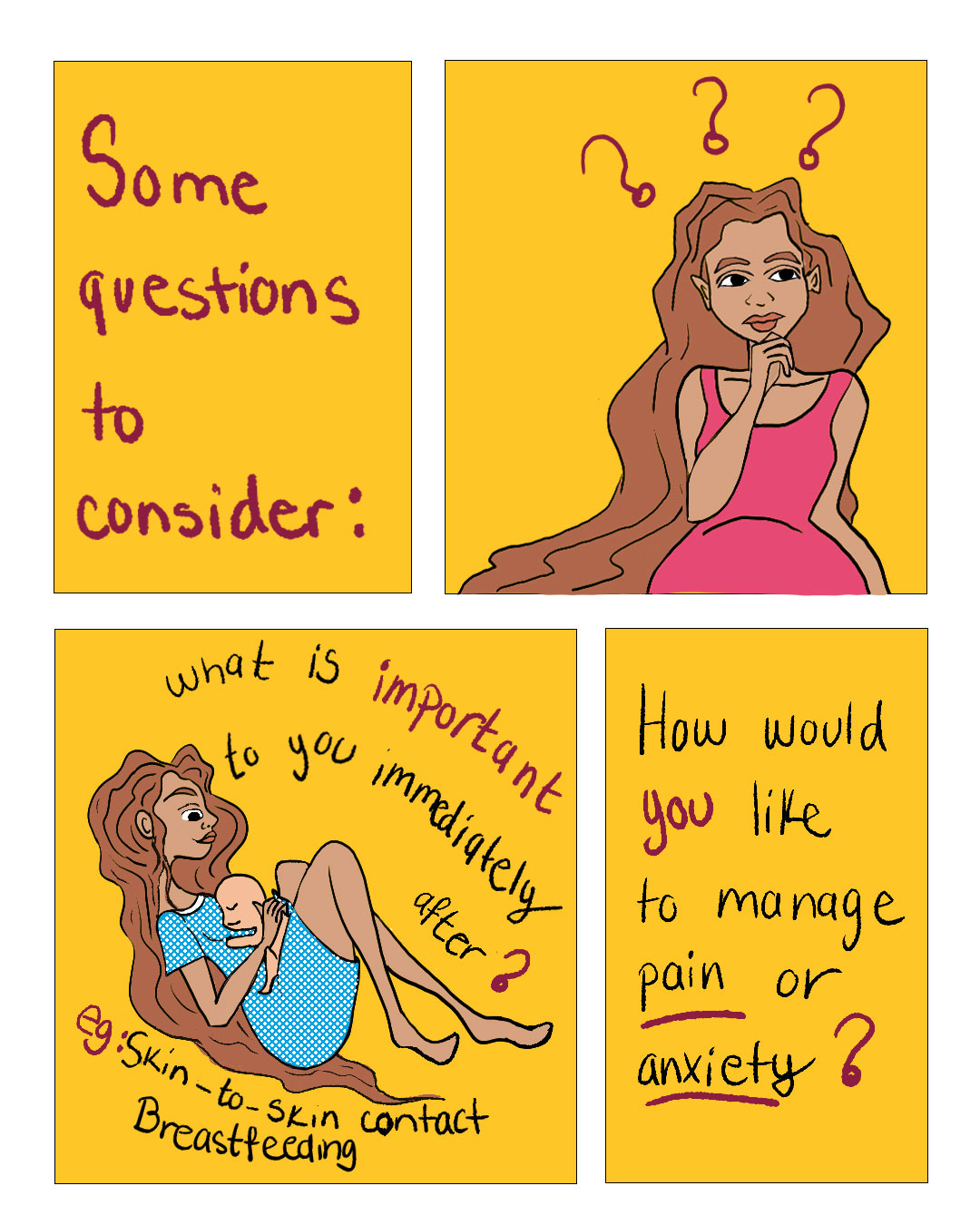

Decisions about a C-section—like, Do I want to have anti anxiety medication which can cause memory loss? or If I have extreme pain, how do I want my provider to handle that?—you shouldn't be making those decisions when they're happening. You should be thinking about them and having conversations about them throughout the pregnancy.

MAL: What do you wish those conversations with your providers had looked like, and when should they have happened?

RS: What I wish my providers had done was talk to me about my priorities for the birth, and then explored with me how those could be honored, no matter how the birth went. I wish that we'd had conversations about, for example, What happens to you when you're scared? I don't think a single provider ever asked me that.

From the provider's perspective, it's really difficult to accomplish that level of education and conversation during very short visits, where they have to accomplish so much. But another way a provider could have brought this up is like, OK, if you do have a C-section, what would be some things you would want to make sure happened in that operation, provided that you and the baby were stable? For instance, you can have skin-to-skin with your baby in the operating room, you can breastfeed in the operating room.

MAL: When you started asking people questions about their C-sections, what are some of the themes you came across?

RS: One of the really big themes was Nobody told me about … let's say, how the operation would actually go, or about very common aspects of recovery. Being kept in the dark adds this extra level of frustration and sadness and isolation.

MAL: Black women are more likely to give birth via C-section, and they also have a maternal mortality rate more than 2.5 times that of their white peers. The popularization of the C-section in the U.S., as you document in the book, is rooted in slavery. How does race play into how C-sections are practiced?

RS: What's so important is that it has nothing to do with biology, there's nothing about Black women that makes them more likely to need a Cesarean than somebody from another ethnicity.

It's racism across all levels. So you have, for instance, social inequities, social determinants of health. There's a gap between the desire that people have to see midwives and their availability for every single ethnic group. But the gap is greatest for Black women. So Black women really, really want to see midwives, and they really, really cannot access them.

What does that have to do with C-section? Seeing a midwife is associated with [being] less likely to need or have a C-section. Even going to a hospital where midwives practice is associated with lower C-section rates. So simply because of where I live, or the kind of insurance that I have, I'm more likely to be funneled into higher intervention, more medicalized care, whether I need it or not.

Then you can think about the impacts of weathering. Black women have been exposed to the stresses of racism throughout their life courses, and that means that their bodies have literally been weathered by having to deal with this—particularly if you think about the cardiovascular stresses. And then thinking about interpersonal racism, there's so much evidence that even in the same hospital, providers will treat Black women differently from white women.

Well-Informed: Related stories from the ASU Media Enterprise archives

How has technology changed what medical interventions we deem necessary during childbirth? In this 2018 essay for Zócalo Public Square, Jacqueline H. Wolf explores the complicated answer to that question. She zooms in specifically on the electronic fetal monitor, introduced in 1969.

Plus: Rachel Somerstein recently wrote for Zócalo Public Square on what it would take to bring the U.S. C-section rate down. “To make birth, regardless of how it occurs, better for everyone,” she writes, “we need to reimagine the systems that surround it.”

And in case you’re still hungry for more: What happens if your hospital falls victim to a ransomware attack while you’re in labor? In this article for Future Tense, Josephine Wolff contrasts two examples of mothers giving birth during medical ransomware attacks, with two very different outcomes. It’s a helpful guide to what patients should know about cybersecurity risks—and what hospitals should do to protect against them.

Well-Versed: Learning resources to go deeper

For a deep-dive on all things reproduction, check out Embryo Tales, a part of ASU’s Ask a Biologist. Created from encyclopedia articles from ASU’s Embryo Project, these stories are digestible explorations of everything from how fast embryos grow to what happens when a pregnant person and fetus have incompatible blood types. (And much more!)

Well-Read: News we’ve found useful this week

“31 Million Americans Borrowed Money for Health Care Last Year: Poll,” by Lauren Irwin, The Hill, March 5, 2025

“What E.R. Doctors Wish You’d Avoid,” by Jancee Dunn, The New York Times, Feb. 21, 2025

“Vitamin A and Measles: What the Data Show (and How to Talk About It),” by Katelyn Jetelina and Kristen Panthagani, Your Local Epidemiologist, March 12, 2025

“5 Years After It Was Declared a Global Pandemic, a Look at COVID-19’s Impact,” by Geoff Bennett and Karina Cuevas, PBS News, March 11, 2025

Covid Pandemic Anniversary: 15 Lessons Scientists Learned About Us,” by Claire Cain Miller and Irineo Cabreros, The New York Times, March 11, 2025

Well-Advised: One thing that’s improving our health

Will Humble, executive director of the Arizona Public Health Association, shares changes that have helped improve his sleep:

After I turned 60, it was harder for me to sleep through the night, and I just wasn't getting enough sleep. Not from anxiety or whatever—I was just getting sleep deprived.

My changes were to read an actual magazine or book for 45 minutes before bed—not a screen (usually The Economist magazine). We added a humidifier to our bedroom too, and that helped, I think. I went and bought foam earplugs which I wear every night—so the sound of the ceiling fan, for example, doesn't wake me up.

What’s helped your sleep? Share your tips in the comments.

Well-Defined: Word of the week

Maybe you’ve heard a doctor say they’re going to prescribe you something “prophylactically.” The first time I heard this word, my mind went blank. “Prophy … what?” But it’s actually pretty straightforward: It just means preventatively.

There are lots of examples of prophylactic (or preventative) care: vaccines, blood tests, cancer screenings, dental care. You may have also heard of the drug PrEP, which can help prevent HIV: It stands for pre-exposure prophylaxis.

Well-Aware: Setting the record straight on health myths

It’s a well-worn pattern: After an act of horrible violence—a grisly murder or a mass shooting—media attention focuses on the perpetrator’s mental state, and specifically, whether they were diagnosed with a mental illness. This often reinforces the idea that there’s a link between mental illness and violence, and stigmatizes people with mental illness. But, are the two really connected?

To answer that question, it’s important to start with some numbers. First, one in five Americans experiences mental illness each year, according to the National Alliance on Mental Illness; one in 20 experiences what’s classified as a serious mental illness, such as schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, or major depression. In these statistics, we can see ourselves, our family members, and our neighbors, and research shows that people with mental illness are more likely to be victims than perpetrators of violence. In other words, the majority of violent crimes are not committed by people with mental illness, and the majority of people with mental illness don’t commit violent crimes.

The factors that contribute to violence are complex for anyone—including for those with mental illness. As the American Psychological Association noted in a 2022 article on the topic, when people with serious mental illness do commit acts of violence, their mental illness is often intertwined with other risk factors, like “co-occurring substance use, adverse childhood experiences, and environmental factors.”

The takeaway? Violence is often circumstantial, not inherent. That’s good news, because it means there are things we can do to expand access to care and create safer communities for everyone.

Do you have a question or topic you’d like us to tackle? Would you like to share your experience with a topic we’ve covered in this newsletter? Reach out at any time—we’d love to hear from you.