Interview: What you should know about health care costs, according to a doctor and financial planner

Doing Well interviews Carolyn McClanahan, a physician and certified financial planner.

The U.S. spends a tremendous amount of money on health care: as of 2023, $4.9 trillion per year, which averages out to some $14,570 per person. And while we vastly outspend other high-income countries on health care, we’re not getting much bang for our buck—we perform worse than comparable, lower-spending countries on measures like health outcomes, access, and efficiency. Put another way: Despite spending the most per capita on health care among comparable high-income countries, we have the lowest life expectancy at birth, the highest maternal and infant mortality rates, and the highest rate of people with multiple chronic conditions.

Americans, meanwhile, are often anxious about how they’ll pay current or future medical bills. A poll from the health research group KFF found that 73 percent of adults were very or somewhat worried about being able to afford the cost of health care services.

As Tax Day creeps up and many of us are thinking about our finances, I spoke with Carolyn McClanahan, a physician and certified financial planner, about the intersection of money and health, and the steps we can all take to plan for and navigate health care costs. We discussed how health care can affect your tax bill, how to assess different insurance plans, and how to ensure you’re not being overcharged for care. Our conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

Jump ahead:

Mia Armstrong-Lopez: A lot of people get overwhelmed thinking about health and how it impacts our finances, and there are lots of things that are out of individuals’ control. What is a first step for people who may feel overwhelmed, but want to be proactive?

Carolyn McClanahan: The most important thing is being intentional about how you spend money. Too many people don't understand how or why they buy certain things or how they're budgeting. I have people break spending down into: thoughtful needed spending, thoughtful wanted spending, and thoughtless spending. Understand how you're spending and get rid of the things that aren't important, making sure that you are living below your means.

MAL: It sounds like you're proposing a bit of an audit. How do you recommend people start looking into and classifying their spending on health specifically?

CM: Advisors and the public always ask me: How much should I budget for health? How can I plan for health care costs in retirement? The sad thing is, we can't predict the future. So what I tell people is, you have to control what you can control, and that is how to be a good health care consumer.

You have two types of people, it's a bell-shaped curve: low health care users and high health care users. The first thing that people should do is understand their health care mindset: How much do I like to go to the doctor?

Figure out how much you pay out of pocket for health care, and [use that to determine] what you need to save to afford the type of health care you want in retirement—[taking into account inflation] along with your health insurance premiums and an emergency budget.

MAL: It sounds like it’s important to understand how you interact with the health care system out of choice, and then how chronic conditions or other factors may necessitate different interactions with the health care system.

I want to talk about how health care expenses affect tax bills. Let’s start by breaking it down on a really general level: How does what I spend on health care affect my tax burden?

CM: It depends. Your [tax deductible] medical expenses are limited to [those that exceed] 7.5% of your adjusted gross income. So let's say you make $100,000—you can't itemize [and deduct] your medical expenses unless those medical expenses are over $7,500. If you have $10,000 in medical expenses, the first 7.5%, or $7,500, is not deductible, so only $2,500 of your $10,000 in health care expenses would be deductible. They have to be qualified medical expenses. The IRS has a list: going to the doctor, dental, vision—those can all be deducted. Long-term care counts if you qualify for long-term care needs. All of those have to add up to a significant amount, though, for you to be able to deduct them.

The other place where health costs can be deducted is if you're self-employed. If you are self-employed, you can have a self-employed health insurance deduction. So the amount you're paying in premiums can be deducted against your self-employment income.

If you get your care through the Affordable Care Act, if your income is low enough then you can get tax credits to help pay for that health insurance. Especially if you're a self-employed person, or if you're an early retiree, it may be possible to structure your income so that you can maximize your tax credit. So you want to talk to an accountant about that: How can I get the best tax credit to help pay for my health insurance?

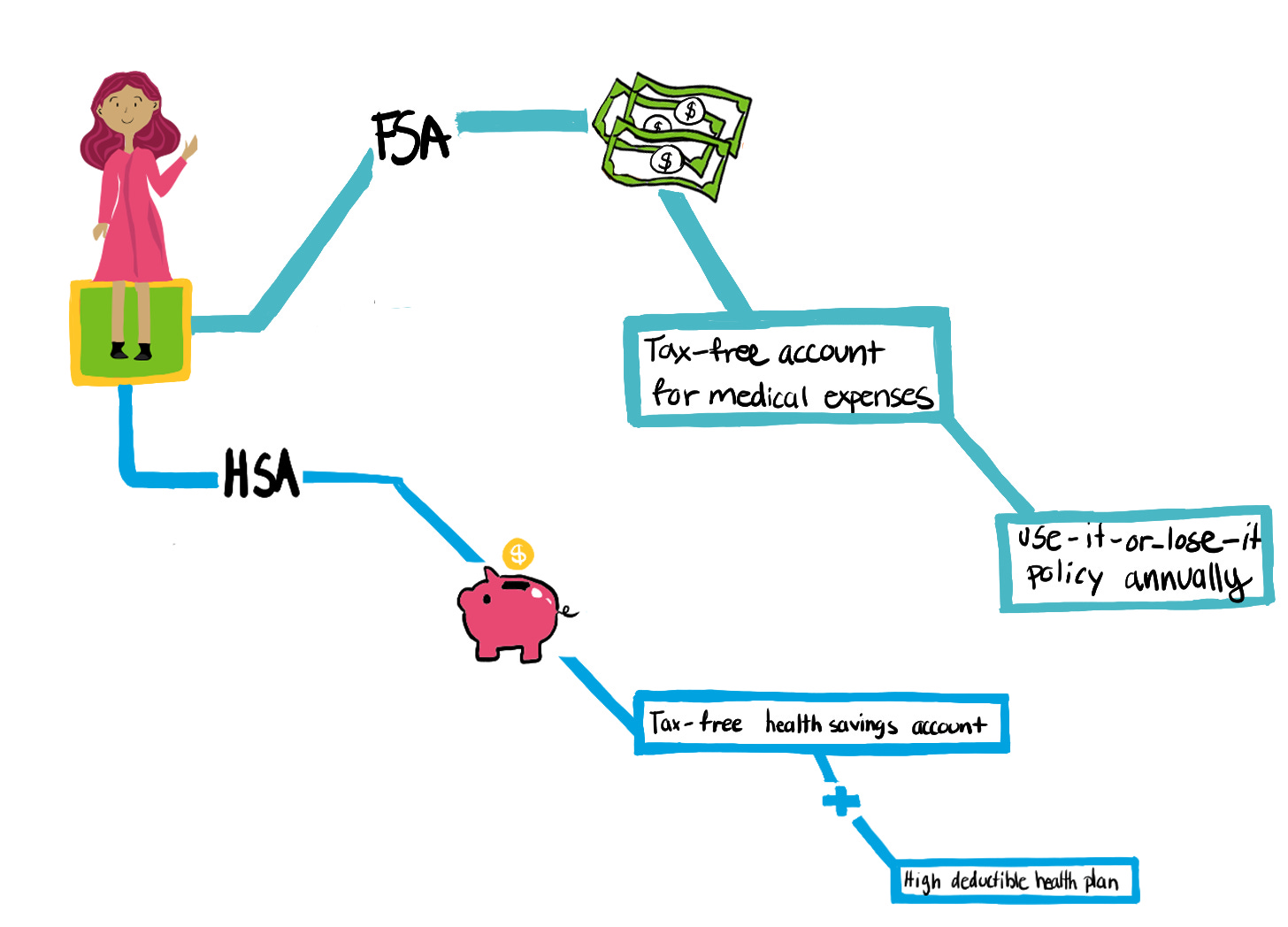

MAL: What are health savings accounts and flexible spending accounts, and how do they play into taxes?

CM: A flexible spending account is something your employer offers where you can put a certain amount of money away each year toward health care expenses that are not paid by your insurance. The problem with flexible spending accounts is it's a use-it-or-lose-it. So let's say you withhold $3,000, but you only incur $1,000 of health care expenses—you could lose that $2,000. So make sure, if you're doing a flexible spending account, that you'll have stuff to spend it on.

Most employers are moving away from flexible spending accounts, and they're offering their employees health insurance that qualifies for a health savings account. Those have become more popular, you can fund them at a much higher level, and you get a nice tax deduction for funding those health savings accounts. The beautiful thing is if you don't have any health care expenses [that year], it can build up tax free for future health care expenses. If you can avoid touching it, when you actually retire, you can have a big pot of money set aside that you can pull out tax-free for health care.

The other nice thing about health savings accounts is that if you are, let's say, 40 years old and working, and you have expenses of, say, $4,000, you don't have to pull that money out of the health savings account. You can pay out of pocket, and then you can choose to let the health savings account grow, but save all your receipts from the prior years. Let's say, over the next 25 years, between age 40 and 65, you spend $4,000 a year on health care expenses. So that's $100,000 in health care expenses over 25 years. When you're 65, let's say your health savings account is worth $500,000, because you did a great job saving, maximizing it, and investing it.

Then you can pull that $100,000 out tax-free to reimburse the health care expenses that were not reimbursed before.

You've got to keep really good records. I have people keep a nice Excel spreadsheet, scan the receipts, and have a year-by-year record of all their health care expenses that were not reimbursed. The one caveat is, you never know if they're going to change the law on that. So just be aware of that possibility.

MAL: It sounds like you recommend an Excel spreadsheet and digitizing receipts for health care expenses. Are there other tools you would point people to make sure they're tracking these things?

CM: You have different reasons to track health care expenses. If you're a healthy person, and you're just going to the doctor every now and then, and you're not doing any health savings account reimbursements, you don't have to be so organized. But if you have a chronic illness or serious illness, it's really good to keep what I call a health care ledger, not only about health care expenses, but also what services you actually received.

If you're in the hospital, and they've done multiple tests, or if you're going through a serious illness and a bunch of testing is being done, there are a huge number of medical bills that are wrong. So if you keep a nice ledger of when you saw the doctor, who you saw, and what was done, then you can compare that to your bill. If you've kept good records, and there's a problem with the bill, it makes it a lot easier to get it resolved. You're also tracking your health care expenses, so if you do have an expensive illness where you can itemize, you're not scrambling come tax time trying to get all those receipts.

MAL: If you're in the health care system, it can feel like you're suddenly pushed onto a rollercoaster of different tests and services, and those bills can really add up. What are your recommendations to make sure that the things we're being charged for and the services we're receiving are necessary, and are a good health investment?

CM: One of the things I teach people is how to be an empowered patient. The sad thing is that the health care industry rarely treats us like patients anymore. We're consumers. And so since they're going to treat it like a business, we need to treat it back like a business. Health care costs a lot of money, so patients need to be better health care consumers.

There are a couple of tactics. First off, I want to stress almost everybody in the health care system, they're good people. They went into it for the right reason. It's the system that's broken, and it's breaking people down. So always go to your appointments assuming that your doctors and nurses want the best for you.

Atul Gawande wrote a book called Being Mortal; in it he talks about the different types of doctors. There are paternalistic doctors, who just say, “Honey, take this pill and call me in the morning, because you'll be better.” Then there's the informational doctors, who say, “Here are all your choices, make one.” The collaborative doctor actually helps you think through all those choices, and they understand what your values and goals are. So you want a collaborative doctor, because they're the ones that are going to help you make the right decisions, which affects the type of care you're going to receive and the cost you're going to pay.

The next thing is always to understand what the doctors are doing, and why. Once you're diagnosed with a disease, that disease is yours, and it's up to you to understand it, and to understand what your part in taking care of your disease is. So when you go to a doctor and they say, “Oh, we need to do these tests,” the number one question I'd make sure you ask is: “How is this test going to change what you do for me?” If they can't answer, then ask, “Is that test really needed? Because I have a $10,000 deductible, and I don't want to do tests that are not needed.”

If testing is ordered, always make sure that you're staying in-network, because out-of-network costs are much higher than in-network costs. So always say, “Is this test in my network?” and write down in your health ledger who said it was. That way, if you get dinged, you can fight back.

It's the same with medications. Doctors just will write what they think is right, they may not check your formulary [a tiered list of medications covered by your insurance]. So if you get to the pharmacy and the pharmacy says, “Oh, this drug is $500 a month,” say, “Is there a generic or a substitution my doctor can make?” Don't be afraid to ask questions.

MAL: Choosing a health insurance plan is one of the biggest health-related financial decisions out there. Some people work with an employer who gives them different options to choose from. Could you walk us through any financial mistakes people tend to make when choosing a health insurance plan, and tips for navigating that choice?

CM: It's important to make sure that you understand your health habits, and which plan that fits into. So, for example, an HMO [health maintenance organization] plan that your employer offers is going to be cheaper, but then that requires you to go to a primary care doctor if you want to go to a specialist. If you have a great primary care doctor who you trust to do things for you right away, then it's usually not an issue. However, if you're the type of person that doesn't want to see a primary care doctor, you want to be able to go to whatever specialist when you want to, then you would want to choose a PPO [preferred provider organization] plan.

Employers usually offer a flavor of both an HMO, a PPO, and a plan that allows you to do an HSA. The health savings account-based plans have to have high deductibles, so if you're going to have a problem funding that health savings account, and if you get sick you're not going to have the money to meet those deductibles, then you might want to choose one of the copay plans.

If you are self-employed and picking plans off the Affordable Care Act, it's important for you to pick plans that your doctors are on. I recommend people to use a navigator to help them sign up for the plans. You can plug in all the doctors, plug in all your medicines and see which policies will cover your doctors and your medicines.

MAL: You help clients think through end-of-life care and expenses. What are advanced directives, and what implications do they have for the financial aspects of end-of-life planning?

CM: End of life is when health care expenses can go up tremendously. Sometimes, if we're not thinking through about what's important to us about health care, not only is it expensive, you end up getting care that’s harmful, painful, that you don't need, and had you discussed your health care wishes with your family and your doctors, you would have gotten better health care at a lower cost. That's where advanced directives come in.

Prepare for Your Care is a free advance directive legal in all 50 states. It actually makes you walk through what's important to you about quality of life: What do you want your health care surrogate to think about and know when they're making health care decisions for you? By having these good advanced directives, sharing what's important to you about quality of life, it keeps them from doing things that shouldn't be done.

Do you have a question or topic you’d like us to tackle? Would you like to share your experience? Reach out at any time—we’d love to hear from you.