Interview: How to understand the technology used in your health care

Doing Well interviews Mara Aspinall, an expert in medical diagnostics and technology.

Around 70% of health care decisions are made based on the results of diagnostic tests, according to the World Health Organization. These tests—which include everything from a blood test to a colonoscopy to an MRI to a pregnancy test—help health professionals detect, understand, treat, and monitor health conditions. Diagnostic tests are a little like the headlights on your car—without them, we’re stuck driving in the dark.

Despite the key role diagnostics plays in health care access and decisions, many of us aren’t aware of what happens in the in-between space after we take a health test but before we act on its results. To understand that in-between space, and the broader diagnostics field, I spoke with Mara Aspinall, a professor at ASU’s College of Health Solutions and the cofounder of ASU’s biomedical diagnostics program. Mara is also a partner at Illumina Ventures and the coauthor of Sensitive & Specific: The Testing Newsletter, published on Substack.

We discussed how technology is shifting the ways we test and treat disease, and the questions you can ask after a medical diagnosis. Our conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

Jump ahead:

Mia Armstrong-Lopez: What do we mean when we talk about diagnostics?

Mara Aspinall: Diagnostics—or as we call it at ASU, biomedical diagnostics—is medical testing to look at a person’s state of health. And with that state of health, we can make decisions about what to do next.

I think about it as five different categories: It's screening—mammography is a great example of early screening that goes out to millions of people who have no symptoms. Secondly, it's early diagnosis: Okay, somebody has symptoms. Are they likely to have a disease?

Next is the actual diagnosis. Then it's what's called prognosis: What type of disease or condition might the person have? All diseases are not the same. Cancer is a great example: There are different types of cancers—different kinds of breast, lung, or any other type of cancer—that have a good or not-so-good prognosis. Is it the type that is very difficult to treat or easier to treat? And lastly, what we call monitoring disease: How has the treatment worked or not worked?

When I talk about monitoring, we can talk about a test called an MRD test—minimal residual disease. I'll stick with the cancer analogy: For somebody undergoing chemotherapy and radiation for cancer, we presume today that everyone gets roughly the same therapy, six rounds of chemo and eight weeks of radiation therapy for each disease type. There's an average. That's great if you're average—but most people aren’t exactly average, we're more or less. And so this test looks for as little as one single cell that continues to be in the body. And when that test is negative, then there's a much more informed decision to stop therapy. If the MRD test shows there are still cancer cells, even if the average is six rounds of chemo, they'll say, “No, we want to do seven or eight.” This new approach can help more precisely personalize and test along the way to get the highest chance for remission—or even, in some cancers, cure.

MAL: It's an example of how technological advances can impact people's lives by personalizing medicine. What is personalized medicine?

MA: Personalized medicine, sometimes called precision medicine, is the core of treatment today. It is the combination of testing with the ability to be as precise as possible with the patient and diagnosis.

A good example is breast cancer: 50 years ago, breast cancer diagnosis was not personalized at all. It was the hallmark of a lump or a tumor in the breast. We now know there are different types of breast cancer, all different subcategories of disease. What is the subtype of breast cancer? And therefore, how should it be treated? In the old days, breast cancer was treated the same, with typically a radical mastectomy and maybe follow-up treatment. We now know that some tumors respond to hormones afterward, some don't; some people respond to chemotherapy, some chemotherapy is more dangerous than the breast cancer. So all the testing makes the diagnosis as accurate and as precise as possible.

MAL: There are so many different tests and technologies. How can someone understand the technology being used in their care?

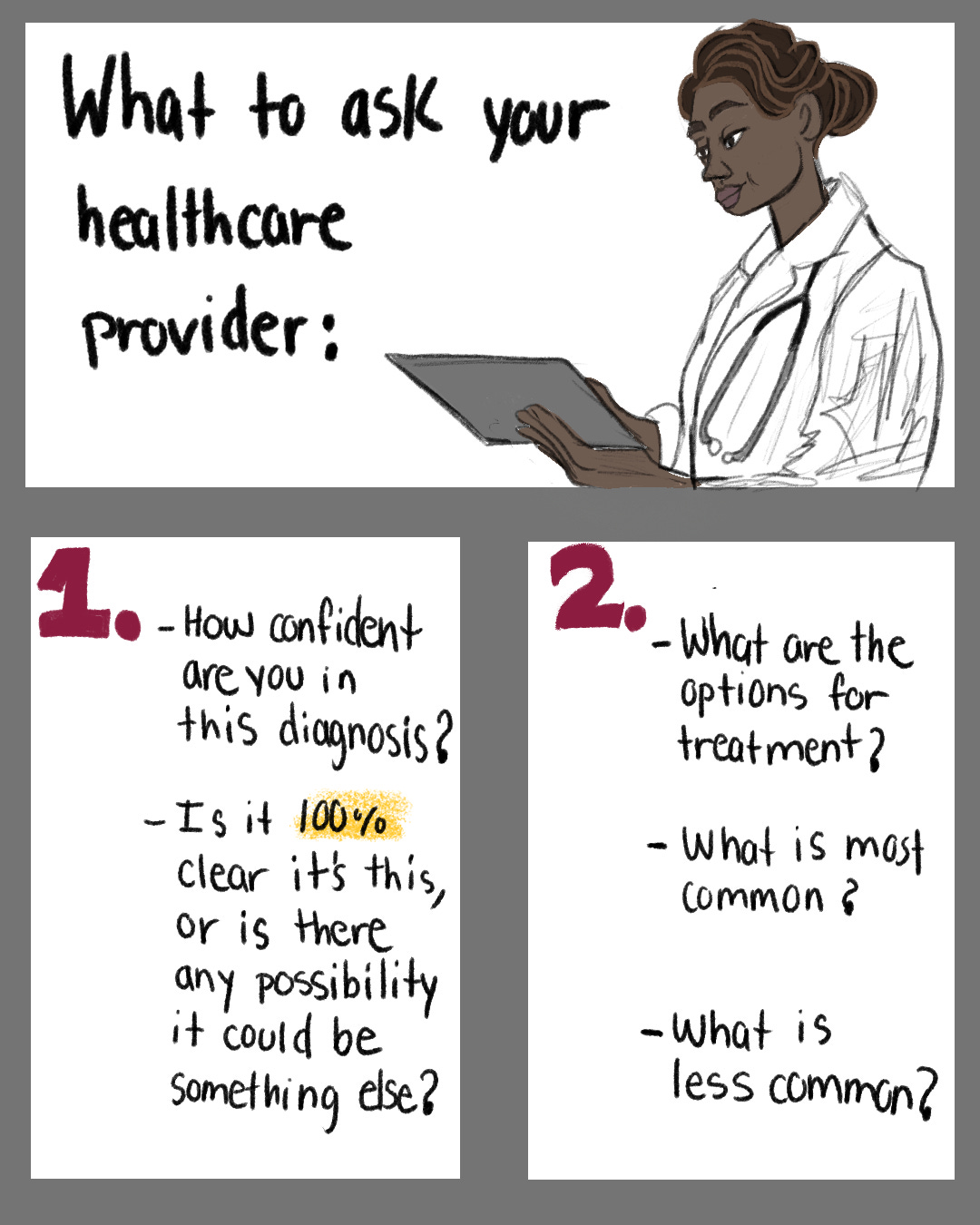

MA: The core is to be asking questions. When you get a serious diagnosis, you can't expect to have all the questions ready at the moment. Serious doesn't always mean life-threatening, it just means something that changes how you go about your life.

The first piece is to go with the physician to ask: How confident are you in this diagnosis? Is it 100% clear it’s this, or is there any possibility it could be something else?

Number two, I would ask: What are the options for treatment? What is most common? What is least common? If a physician knows one aspect of treatment, because that's the treatment they've used before successfully, they might guide all their patients to that treatment.

The third question I would ask is: Is there anything unique about my diagnosis? Is there anything that interacts with the fact [for example] that you have diabetes or don't have diabetes; that you've had—or have never had—cancer in the past?

Lastly, I would ask: What are the core risks of no treatment, and what are the risks of the individual treatments that the doctor is recommending? When I say risks, it’s not always life-threatening risks; you can put side effects into that same bucket, so you know what to expect moving forward.

MAL: That ties into monitoring disease. Sometimes people will live with a disease for many years, or for their whole lives. What should people ask when it comes to a physician’s plan for monitoring health and disease?

MA: Unfortunately, in our current health care system, doctors don't always have the resources to stick with a patient to monitor long-term. A patient needs to understand who the physician is that they will see moving forward. If it's a course of treatment that's six months, ask: Who do I see after the six months?

Again, I'll use the [cancer] example: You'll be with one doctor for a very intense period. Then, if you go back to your general practitioner, will that person know how to monitor you going forward? I would ask: Who's going to take responsibility for me after the treatment? What are the signs that you would look for to say that the treatment is working? How frequently do I need to get an update on my condition?

The last thing I would think about discussing with your physician is: How will the physician monitor you? Is it a CT scan, an MRI, something that you have to interact with the medical establishment to do? Or is it self-reported, like energy levels? Is it something you can test for at home?

MAL: Technology has given us access to new sources of data on our health. How do you know what to pay attention to?

MA: I wish I knew an easy answer to this question, because it is highly personal. Let me acknowledge that [around] 25% of the country does not have a regular general practitioner to ask this question—but for people who do, ask: Given my age, given my condition, what is the most important thing that you need to see?

It's very easy not to ask and assume the health care professional will take care of you. And it’s not that they don't want to—but they have a lot of people [to take care of]. You've got to ask the physician what to look for.

MAL: For someone who is not looking at diagnostics professionally, but is interested in keeping up-to-date on the technology, what recommendations do you have?

MA: There's no better time to keep up with technology as there is today. There are a lot of great sources out there; I would suggest picking a few authors you trust and sticking with them. Ask your physician, What does he or she look for? What are the key sources of information?

The biggest challenge is not overreacting to one data point. There is so much information; you've got to find sources that you trust. If it's something very specific to you, go to the patient association—that is often one of the very best sources of data that's relevant to your disease, your condition, your age. Don't be afraid to make a call—I've been really impressed over the years that you can call these patient associations and ask them to help point you in the right direction.

MAL: Many of us got familiar with at-home testing during COVID. But there are lots of other conditions with potential for at-home diagnostics. What is the role of at-home testing in the diagnostics field currently, and where do you see things going in the future?

MA: At-home testing has fundamentally changed since the COVID pandemic. There aren't many good things to say about COVID, but one of the things that I believe is positive is that it gave populations around the world the ability to test for disease themselves at home. It happened because of need. But why was it possible? Because the technology worked and was able to be made simple enough, cheap enough, and accurate enough to be done at home.

You probably remember the lateral flow tests, where you get some of the mucus that was on the lining of your nose, and use that in a liquid to test for COVID. What was exciting this past winter is that those tests now not only test for COVID, but also test for flu A and flu B. What does that do? It enables any of us, when we're feeling really really lousy, not to have to get up and go to the doctor, not to expose other people, but to get that test done at a reasonable price at home, and then get the therapy you need—or frankly, just stay away from others, so you're not spreading the disease.

We also saw in the last year a huge increase in other types of tests that could be done at home—STI testing for syphilis is one example. I believe we will see far more tests that are done at home with less invasive samples. This will be not only nasal mucus, but saliva and even breath. And as these tests are miniaturized, you're going to be able to get them at your physician[‘s office] or at the drugstore, bring them home, and get an answer in real time, or very soon afterward.

MAL: Are there certain diseases or conditions that we're not currently testing for at home, but we likely will in the next five years?

MA: The possibilities are quite large. First, we're going to see more tests with less invasive samples. Today there are tests through saliva, sweat, urine, and blood. But what we're going to see in the future are things like voice—you'll be able to talk into an app and understand, Is this Parkinson's? You'll be able to cough into an app, and using AI and machine learning the system will know whether that cough is COVID, bronchitis, or tuberculosis. I’ve already seen a test on menstrual blood to be able to look at endometriosis. These creative tests combine the less invasive sample with software technology.

I think we will see far more hormonal testing. We've already seen some allergy testing, and I believe that will expand and be made easier, cheaper, and still accurate at home.

The challenge, though, is once you have these results—so what? And that's what scares a lot of physicians. As strong as these tests are, many of them require interaction with a physician afterward, so we need to create systems to ensure that even though you're doing the test at home, you talk to a health care professional about treating or understanding the results of those tests.

MAL: It sounds like a systems question: How do we update our medical systems to accommodate that shift?

MA: That’s right—and it's changing. Artificial intelligence is what everybody's talking about, but even in the simplest way, there are many states today that do not allow a physician to put in the medical chart a test that you took at home.

We as a society need to figure out: Where are the guardrails with this data, and how can it be reported?

MAL: In broad strokes, how is artificial intelligence changing the field of diagnostics?

MA: Radiology is one example that will continue to use aggressive machine learning and AI. Another is integrating results from patient reports. As is very typical with complex diseases, a patient will get blood tests, they'll get urine tests, they'll have a radiology test. They might have an EEG and a chest X-ray. And the physician has to put all these together and see how they interact. I think that's the next area where AI will be used in diagnostics.

Beyond that, a physician may look at your data and then say, How does it compare?—not just to his or her practice of 25 people with the same disease, but to 25,000 people or 25 million people around the world.

MAL: No technology is 100 percent perfect. With the diagnostics tests we take, there can be false positives, mistakes, and errors in the interpretation of results. AI can also get things wrong. What questions should patients ask to ensure that they can be confident in their diagnostics care?

MA: It is very fair to say AI is not perfect; it's important to understand how it's trained. But humans are not perfect either. It is critical to ask: How was the diagnosis made? How was the test done?

MAL: Another accelerating technology is wearable technology. Many of us have smart watches or smart rings, different tools that are tracking our sleep, our stress, our movement. How will the increase in wearable technology affect diagnostics?

MA: The use of wearables has exploded—it's not just the watches, but the rings, the bracelets, and most recently we wrote about wearable pajamas that take a look at all your bodily functions when you sleep. So I think wearables are here to stay. But as exciting as that sounds, most wearables are short-lived with individuals—they use them for 90 days, sometimes 180 days, and they're not using them forever. Secondly, the data from wearables are not always reported to the physician. There are wearables that tell me how much sleep I got last night and how many steps I walked—my doctor doesn't need to know that. But if you have a wearable that looks at a pacemaker, it's pretty important that it is seamlessly integrated for a physician who is actually looking at it. I'm excited about wearables, but I don't think it's seamless communication now.

One of the fundamental truths of diagnostics today versus 20 years ago is that the industry used to focus on getting one data point correctly. What is my blood glucose level today? What is my blood pressure today? What is my heart rate today? What we found as an industry is that one data point is frankly not good enough, because my one data point may look high compared to your one data point. It's really the average, it’s the continuous monitoring that makes the difference. I have one child whose temperature runs 1 to 2 degrees high. If you only looked at him on one day, you would say he has a fever. But when you look at the fact that it's like this for three months, that's what his norm is. It's important for each of us to know what our norm is, and for our physician to acknowledge that.

MAL: You're constantly reviewing new research and diagnostics technology. What are the developments that will impact our health most profoundly?

MA: I'm going to give you the five things that I see as the best things that have happened in diagnostics in the last few years, and why I believe with each of them we're only just seeing the beginning.

First, home testing. I believe home testing will gain more and more approvals, we'll see far more tests for STIs and other infectious diseases in the future.

Number two: What's called liquid biopsy. Many people know what a biopsy is, which is a very invasive test looking at the cells and a particular tumor or growth in the body. One of the biggest changes has been what's called liquid biopsy. Instead of going to that tumor itself, we get a sample of the person's blood, and we can see what's happening with a particular tumor, whether there are other tumors in the body. Why is that? Because the tumor sheds part of its DNA into the blood, and each type of tumor sheds a different kind of biochemical marker. I think liquid biopsy has been firmly established in R&D, and will be increasingly used in clinical care, including early diagnosis.

Number three is AI. We talked about the importance of AI, not only helping the patient get a faster answer but most importantly in the short term, helping the physician wade through so much data and put it together in an orderly way. AI and machine learning can make the diagnosis, or at least the possible diagnosis, more clear for the physician, and therefore the patient.

Next, the focus on neurodegenerative diseases like Alzheimer's, dementia and Parkinson's. Only five years ago, we could not diagnose Alzheimer's or Parkinson's before symptoms started, and once symptoms start, it's very hard to treat. There's no one perfect test today, but we have made so much progress in taking somebody with mild cognitive impairment and diagnosing them. Then, along with the huge change we've had in therapeutics, we now have drugs that might work effectively without too many side effects. Are they perfect? Are they going to get rid of the disease? No, but a huge step forward, and we will see more.

Lastly, and what my firm Illumina Ventures focuses on, is what we call Genomics 3.0—the intersection of genomics, proteomics, epigenomics, and AI delivering on the promise of large-scale personalized medicine. We're not just looking at the DNA of the tumor, we're looking at the RNA, we're looking at the gene mutations, we're looking at the proteins. No matter how bright the doctor is, they don't have the X-ray vision to understand what's driving specific cells, to look at the dynamics of tumor progression, metastasis, or other disease processes.

Do you have a question or topic you’d like us to tackle? Would you like to share your experience? Reach out at any time—we’d love to hear from you.