Half the population goes through menopause. Why are so many of us still in the dark?

An interview with a leading menopause expert | Plus: What’s “herd immunity”? + How stigma affects HIV treatment

Welcome to Doing Well. Today:

An interview on menopause myths—and how to sort fact from fiction

Word(s) of the week: Herd immunity

Let’s get started.

We Asked: How can we get better menopause care?

Half of the population will go through menopause—a stage in life when a woman’s ovaries stop releasing eggs and menstruation ends, making pregnancy no longer possible. The term menopause refers to the point in time when a woman has gone 12 months without a menstrual period, typically around age 51. In the years before reaching that milestone—a period known as the menopause transition, or perimenopause—the body’s production of hormones including estrogen and progesterone fluctuates and declines, which can cause symptoms like hot flashes and sleep problems that range from uncomfortable to unbearable.

There are hormonal and nonhormonal therapies to address these symptoms. There’s also lots of misinformation about menopause—and plenty of companies and influencers marketing menopause products. If you’re a woman in her mid-40s, you’ve probably seen social media ads for pills, patches, and diets that make big promises to reduce or eliminate menopause-related woes. But it can be hard to know what to believe, and to access high-quality menopause care from a health care provider. Menopause has long been under-researched and overlooked; in one 2019 study, only around 7% of OB-GYN residents reported feeling adequately prepared to help patients manage menopause.

I spoke to Dr. Nanette Santoro—a professor at the University of Colorado School of Medicine and one of the leading experts on menopause and hormone therapy—about menopause symptoms, treatments, and myths. We discussed how to document your experience of menopause and find a health care provider who can give you appropriate care, and what you should know if you’re supporting a loved one through menopause. Our conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

Mia Armstrong-Lopez: What is the menopause transition?

Nanette Santoro: The menopause transition is a period of time that begins on average at about age 47. That's when a woman may first notice that her menstrual cycles, which were previously regular, become more irregular, or she'll skip a whole cycle. That's the beginning of the transition as we now define it.

What is going on in the background is that throughout her life, a woman’s supply of eggs is decreasing. Around mid-40s, that's when either a more than seven-day difference in your cycle length or a skipped cycle can herald entry into the transition. Once a woman goes 60 days without a menstrual period, that places her in the late menopause transition, where the typical symptoms that we associate with menopause seem to kick up.

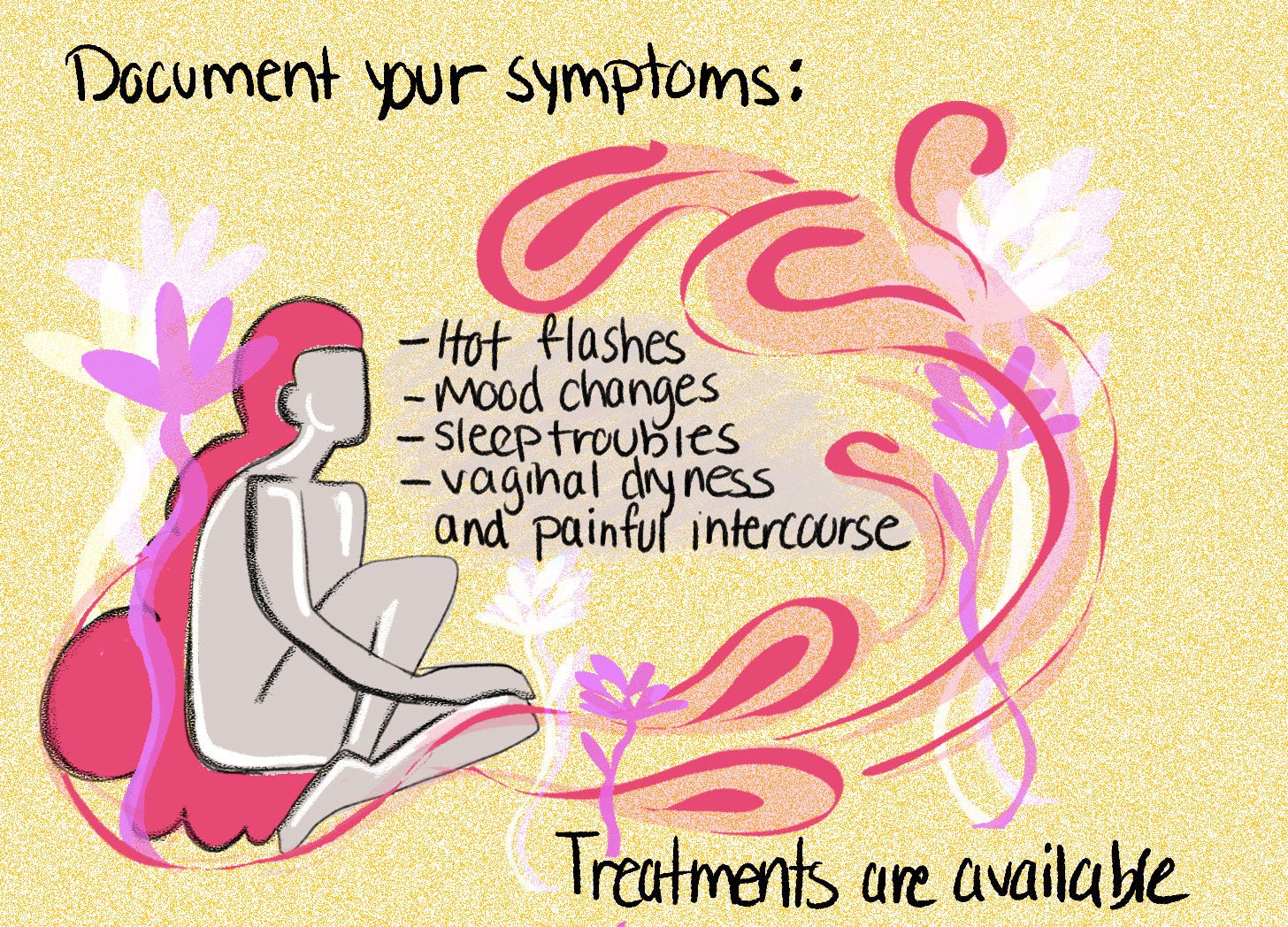

In that late transition time, women will have the most hot flashes—that's the most common symptom and happens to about 80% of women. Other things that will bring women to seek treatment are vaginal dryness, so intercourse can be painful. Women may notice worse sleep. And both depression and anxiety can be more common. Most of those things are treatable with hormones for women who can take hormones. Don't wait until the process is over, because treatments are available.

MAL: Imagine that someone is starting to experience the symptoms you've described. What should they do?

NS: One of the great things to do is to document when symptoms happen in relation to a menstrual period. That can help me when I see my patient in the office and I'm trying to figure out, What's the relationship here? Is it right around the time of her period? That's more suggestive that it is a menopausal thing.

Also prioritize: What is the most bothersome thing? If I could only help you with one thing today—because maybe I can't wipe out a list of seven problems with one treatment—what would that be? And then give me those in order. Sometimes people will bring in a list of 10 things, and then we'll try to get as many as we can, and try to address the priorities.

I have many patients come to my office, tell me what's happening, and then they leave, and they really don't want treatment—they want validation. Others come in and they say, I see these changes are beginning, where am I in this process? How much worse is it going to get, and when do I need to come back? Understand your threshold for treatment; everyone is a little bit different.

MAL: What are the major available treatments?

NS: In the menopause world we have a problem, because there's a lot of things that are not evidence-based. Supplements are not regulated by the FDA. The FDA requires you to prove efficacy and safety, and that is not required for supplements. So it's really buyer beware.

There are evidence-based treatments out there. I very much encourage people to use FDA-approved products because they have gone through the process required to prove efficacy, safety, and proof of claim—if you say it's going to do this, it's going to do it.

For hot flashes and for women that have multiple menopausal symptoms at the same time, the preferred treatment is hormone therapy, because it is the most effective overall, and it will address multiple symptoms. If I have a patient who does not have any contraindications and is willing to try it, and she's got hot flashes, poor sleep, and her mood is not great, that would be my first choice. Hot flashes are important because they're the thing that drives most women to see a doctor about their menopause. If it's just hot flashes and nothing else is really a problem, there's a number of nonhormone treatments. There's now an FDA-approved nonhormone treatment that targets a specific receptor in the brain where the brain's thermostat is located. Blocking that receptor works well in blocking hot flashes.

The other nonhormone treatments were found by serendipity, because the patients who were taking them went back to their doctors—they were all people with bad hot flashes who couldn't take hormones, and said, Whatever you gave me made my hot flashes better. Then their care team got together and said, Hey, why don't we test this? So things that have been tested in clinical trials but are not FDA approved include a number of SSRI and SNRI drugs. One of them, paroxetine mesylate, is approved in the form of Brisdelle as a treatment for hot flashes. Gabapentin is another medication that's used for pain, and oxybutynin, used for overactive bladder, has also been looked at. In some older studies, clonidine, a blood pressure medication, has shown some activity against hot flashes. Those are all nonhormone options, but a lot of them have what we call off-target side effects. So if you're not a depressed person, and I give you an antidepressant, it may put your mood a little bit off in a way that you don't like. Gabapentin can make people drowsy, so it's best used at night, and oxybutynin and clonidine can give you a dry mouth. A lot of these things will have annoying side effects that make them a little harder for patients to stick with.

MAL: What recommendations do you have for someone trying to find the best provider to help manage their symptoms?

NS: The Menopause Society provides specific training. It has a guidebook, and you have to read it and pass the test to become a menopause-certified practitioner. A menopause-certified practitioner is a good place to start for a patient who feels she has menopausal symptoms, because they'll know that they're seeing someone who's knowledgeable in the area.

There are some internists who specialize in women's care. The Endocrine Society and the American College of OB-GYNs have websites and information for patients.

MAL: How can people sort through the information about menopause symptoms and treatments, especially online?

NS: Beware if all that you're seeing are anecdotes, like I tried this stuff, and oh, my goodness, it was the greatest thing ever! Look for the data. It's worthwhile to actually click on links, because I have been to websites that have fraudulent links—they link to nothing, or to something that is not what it was stated to be.

The things that you're looking for in a reliable study is: Is it an adequate number of people? For most menopause studies, 100 to 200 people is a reasonable sample to show that something improved. Is there a placebo control? You need to control the treatment against a dummy treatment, especially in menopause medicine, and especially when we're talking about situations where the symptoms are subjective—there can be a very profound placebo effect.

The next thing you need to see is, How robust are the findings? One study doesn't always mean much. Most of science has to be confirmed—that is the nature of science, it has to evolve as the data come in. Independent confirmation is one of the keystones of science.

MAL: I like that suggestion, because people might not be able to read through a whole academic research article, but you can usually find how many people participated in the study and whether there was a placebo in the abstract (or the summary paragraph) at the beginning of a research article.

What are the most common myths about menopause?

NS: Hormones will cure all problems, all the time, for everyone is one myth. Hormones are the worst thing in the world is the second myth.

One of the other things that is troublesome is that many women feel we tolerate suffering in women that we probably shouldn't tolerate. So my advice to most patients is, if you're not getting an appropriate response to your symptoms, then you need to either ask for a referral or find someone else.

People who look like they have all the answers, those are the ones I'm the most afraid of.

MAL: What recommendations do you have for supporting someone through the menopause transition?

NS: We know that if you have worse hot flashes during your menopause transition, 20 to 25 years later, you have a higher risk of heart disease. That may be because a person who has hot flashes is more prone to heart disease. But it might also be that if you treat them, you can avoid some of that risk later in life. If you have a loved one who's struggling, pointing out that there may be long-term benefits to not just treating the symptoms, but recognizing how she's at risk is important.

Then, you may want to prod them, because you can get a little bit like a boiled frog through menopause symptoms—you just tolerate them. They're getting worse and worse, the water is getting hotter and hotter, and you don't realize it until you really feel bad. Depressive symptoms can become quite serious. If your loved one is showing signs of major depression, you may need to be more active about getting them to help.

Read more from Dr. Nanette Santoro on identifying menopause misinformation.

Well-Informed: Related stories from the ASU Media Enterprise archives

How do menopause symptoms affect women at work? A study from the Mayo Clinic found that 13% of women reported adverse work outcomes as a result of menopause symptoms. The study estimated that menopause symptoms lead to an estimated $1.8 billion in lost work time in the U.S. each year. Learn more in this Arizona Horizon interview on Arizona PBS.

Well-Versed: Learning resources to go deeper

Are you curious about the science of menstruation? Do you want to learn more about hormones like estrogen? Check out Embryo Tales, part of ASU’s Ask a Biologist. You’ll find a free library of helpful resources that will break down menstruation, sex chromosomes, reproductive biology, and much more.

Well-Read: News we’ve found useful this week

“One Type of Mammogram Proves Better for Women With Dense Breasts,” by Roni Caryn Rabin, May 23, 2025, the New York Times

“First FDA-cleared Alzheimer's Blood Test Could Make Diagnoses Faster, More Accurate,” by Jon Hamilton, May 21, 2025, NPR

“Are Protein Shakes Good for You?” by Sara Klein, May 19, 2025, TIME

Well-Defined: Word of the week

During the COVID-19 pandemic—or more recently, with the measles outbreaks—you may have come across the term “herd immunity.” But what exactly does herd immunity mean? Herd immunity is achieved when enough people in a community are immune to a disease—through vaccination or previous infection—that it’s hard for the disease to spread.

You can think of your community as your “herd”: When enough people in the herd take steps like choosing to get a vaccine, they put the brakes on a disease spreading throughout the whole community. This protects others, including young children, immunocompromised people, or people who may not be able to get a certain vaccine. The proportion of the community that needs to be immune to achieve herd immunity varies by disease—the more contagious the illness, the more people need to be vaccinated to prevent its spread.

Want to take action to protect your herd? Check out vaccine clinics in your community.

-Mel Moore, health communication assistant

Well-Aware: Setting the record straight on health myths

Human immunodeficiency virus, or HIV, is a sexually transmitted infection that can damage a person’s immune system, rendering it unable to fight against infection and disease. If untreated, HIV can lead to acquired immunodeficiency syndrome, or AIDS.

HIV is transmitted through bodily fluids—including semen, pre-seminal fluid, vaginal fluid, rectal fluid, blood, and breastmilk. For HIV to be transmitted from someone who is HIV-positive to someone who is HIV-negative, the fluid has to contain a certain viral load, or quantity of virus. The virus also has to make it into the bloodstream of the person who was HIV-negative. This can happen through an open cut or sore; a mucous membrane like those in the rectum, vagina, mouth, and tip of the penis; or an injection from an unsterile needle or syringe.

There are lots of misconceptions around how HIV is transmitted and who is affected, which contribute to HIV and AIDS being highly stigmatized. As of 2022, only 43 percent of American adults reported feeling comfortable interacting with people living with HIV, and 33 percent said that HIV mostly impacts LGBTQ people. Much of this stigma dates back to the epidemic of HIV/AIDS in the U.S. in the 1980s and early ‘90s. In 1981, health officials noticed a spike in cases of what were extremely rare and fatal diseases associated with immunosuppression among gay men in New York. From then on, reported cases were concentrated among gay men, people who inject drugs, and at-risk heterosexuals, particularly among racial/ethnic minorities. In 1982, the New York Times deemed the health crisis “Gay-Related Immune Deficiency,” or GRID. The result was fear and stigma, leading to more confusion and fear around treatment and prevention.

In reality, “HIV impacts people of all backgrounds, genders, and sexual orientations,” Angel B. Algarin, an assistant professor at ASU’s Edson College of Nursing and Health Innovation, told me in an email. According to the United Nations, as of 2023, 53% of all people living with HIV were women and girls. Framing HIV as a disease confined to men who have sex with men or as associated with certain behaviors “deepens stigma,” Angel said, and “blaming individuals for their status ignores structural factors like health care access, stigma, and systemic inequalities that shape risk and treatment access.”

That stigma, meanwhile, “prevents individuals from seeking testing, treatment, and staying engaged in care,” Angel told me. “Reducing stigma is critical to improving health outcomes and controlling the HIV epidemic.”

Accurate information and education can help reduce this stigma, and make our communities healthier. Treatment for HIV, called antiretroviral therapy, can prevent transmission and allow people who are HIV-positive to live long, healthy lives. If you are seeking more information about HIV, or wondering what treatment looks like, here are some resources:

- Mel Moore, health communication assistant

Expert review provided by Dr. Angel B. Algarin, assistant professor at ASU’s Edson College of Nursing and Health Innovation

Do you have a question or topic you’d like us to tackle? Would you like to share your experience? Reach out at any time—we’d love to hear from you.